|

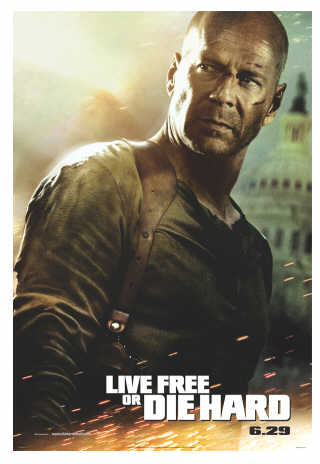

Live Free or Die Hard

by Mitch Finn, MA

It's good every now and then to take in a good car chase movie, and no one quite blows 'em up like Bruce Willis. In the new DVD release of Live Free or Die Hard, he returns to his starmaking role as John McLane, the tough-talking everyman New York City detective with a knack for single-handly foiling large-scale heists and global terrorist imbroglios. The revival of this franchise was meant to capitalize on the paranoiac post-9/11 America; some things have changed for the old man. While on one hand this is one of those big dumb movies with endless pyrotechnics and digital slight-of-hand, it does not fail to offer deeper critical issues relating to the problem with freedom, the status of patriotic dogma, and the disillusionment of action hero in American cinema. It's good every now and then to take in a good car chase movie, and no one quite blows 'em up like Bruce Willis. In the new DVD release of Live Free or Die Hard, he returns to his starmaking role as John McLane, the tough-talking everyman New York City detective with a knack for single-handly foiling large-scale heists and global terrorist imbroglios. The revival of this franchise was meant to capitalize on the paranoiac post-9/11 America; some things have changed for the old man. While on one hand this is one of those big dumb movies with endless pyrotechnics and digital slight-of-hand, it does not fail to offer deeper critical issues relating to the problem with freedom, the status of patriotic dogma, and the disillusionment of action hero in American cinema.

As for the plot: Willis gets called to an assignment that is supposed to be a routine pickup of suspect Matt, a hacker nerd played by Justin "the Mac Guy" Long. A squad of French mercenaries attempts to assassinate the witness, and Willis goes into action to protect the kid. They are drawn into a disaster movie, as it becomes apparent that the entire Eastern seaboard is being shut down by a series of massive computer hacks. Long plays the twenty-first century cyber guy who shrieks the obligatory sidekick kind of "I can't believe we're doing this!" exclamations. Willis, now past fifty, delivers the audience's nostalgia for an old-school kind of hero who kicked butt with unapologetic machismo in the eighties.

The archvillain, Thomas Gabriel, (Timothy Olyphant), looking more like a suave Calvin Klein model than a superhacker, manipulates a series of attacks against McLane and the FBI. He was the guy who created the national web security system after 9/11 and then left because the government would not heed his warnings of serious net vulnerability. His master plan is to orchestrate a ginormous practical joke by pulling off a massive digital robbery from the central financial database. Here is where the plot holes become bigger than Willis' paycheck. If he takes all the money, he would theoretically make the whole country broke. Okay. But really, the dollar would lose all exchange value and become worthless to the robber. It is ridiculous, which is pretty much the point. It is as though these nimrod baddies deserve their comeuppance on the general principle of stupidity.

But there is a more serious issue here that deserves critical attention. In an age of paranoia and unbelief, where identity is in constant threat of theft, this Die Hard presents a different, more rigid society than in the first Die Hard of nearly 20 years ago. It presents a very different view of the human being — one whose life is categorized, specified, and quantified through gigabytes. One's finances, the sum of one's labor and worth are all in the computer. The establishment's fear in the film is losing the numbers, not losing life. The FBI is protecting free enterprise, not individual freedom.

Live Free demonstrates a conflict between the digital citizen and the analog cop, who remains an anachronistic dinosaur in twenty-first century technoculture. Remember, the first Die Hard was very manual, instinctual, caveman- like in its action. It was animalistic; brutal in its bloodletting, expletive-flowing, neck-snapping claustrophobic fury. The new film is tamer, partly done sitting at computers, and partly in explosions. It is more heady, more disembodied, or more accurately, depicting a clash of the brute and the brain.

Which image of freedom is meant to be preserved at all cost? The man, or the numbers; individual freedom, or free enterprise? For us, it is open to debate in the streets. The establishment's choice is clear. But McLane knows nothing of computers, so would go for the former. He has his radio tuned into Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Fortunate Son," among the great anti-war anthems of the Vietnam era. Bingo! That drives the message home. He has his own notion of freedom — he is no patriot and he is not a good soldier. McLane has continual problems taking orders. He's the independent action hero, without complicated ideals, ideology, or beliefs. Because he has no convictions, he is not a rebellious sort either. He's going along just the same, because what else is there to do? Further, Willis acts as if he's still an Everyman,

but with silent recognition that he has an indestructible superhuman quality. Through all the films, Willis gleefully lampooned the old dogmatic American cowboy image with his mocking the likes of Roy Rogers and John Wayne, most notably in his famous one liner, "Yippee-kay-ay, motherfucker!" He is ambivalent about his own role — at once the hero and anti-hero. He is devoted to the job, yet devoid of conviction, as if he is his own counteragent.

The villains, more annoyingly, also lack conviction. They are robbing the finances of the government, not for subversion, nor for a serious attack, but for an epic-in-scale practical joke. There is no religious, or even ideological, conviction. How could they risk these lives, this amount of resources, years of planning, all without conviction of action and belief? Things blow up, and characters pretend to make a point here and there, but end up not making any point whatsoever.

This is the precise condition of our post-ideological age. The action occurs without ideology, portraying a world of conflict without functional belief; a world in contempt for grand narratives and dogma. It is almost the inverse of this year's earlier controversial blockbuster, 300 — that bombastic epic about the battle at Thermopylae where Spartan King Lenoidas' personal guard fought off the Persian hordes. There the ideological war was palpable, some would say even fascist, in its propaganda — orientalist, xenophobic, enlightened, dualistic. It was a clear Manichaean sort of war of absolute good versus absolute evil, all the while being ignorant of its own intolerance. Here, we have the inverse, a world with no conviction, and the film uses pyrotechnics to hide the fact that there is no character and no drama. This only happens because there is no rhetoric, and no legitimate claim to support the dogma of free enterprise without the added façade of higher ideals of individual liberty. Even this empty version of freedom cannot be supported by the hero.

Audiences were rightly suspicious of the antiquated ideology of 300, while Live Free or Die Hard belies its patriotic title. It gives a sharper impression of the ambivalence citizens feel toward their country, a suspiciousness of itself and old ways of believing.

It was only twelve years ago that Arnold Swartzenegger's 1995 film True Lies won the box office gold portraying "good Americans" versus the "evil Islamists." Live Free borrows imagery from the film, (notably in the scene with the hovering jet fighter and the exploding bridge), as though to allude to and bring attention to a contrast with that different worldview of not so long ago. The difference, of course, is that True Lies had a belief in a strong nationalist ideology. It was not surprising that the film, universally banned in the Middle East, now views like government propaganda. Now one is left wondering about the title — was the 'true lie' that Arnold was a secret agent, or does the 'true lie' refer the function of ideological filmmaking — concealing truth?

Although Live Free is efficient at deconstructing old ideologies by its pointless terrorism and carefree heroship, it lacks the dramatic teeth and basic dramatic core of meaning. Its conflict is contrived, petty, and seems to makes little sense. We are left wondering why we are watching, or why we should care.

It's noteworthy that the film deliberately goes to great lengths to not ruffle feathers, demonstrating in vogue Hollywood political correctness. The film was tacked with a deliberate PG-13. While this was an attempt to lure young summer moviegoers, it effectively castrated the traditional hard-R ultra-violent mayhem diehard Die Hard fans had come to expect from John McLane. The FBI chief is played by the Maori actor Cliff Curtis, whose racially ambiguous looks have led him to being cast as anyone ethnic, (including an Arab in Three Kings), as though to rub in our faces that "Ethnic is cool! Arabs are cool! They're not all bad guys!" To top it all, the villain is not a fundamentalist of any sort, nor even a true terrorist as per the cliché Eastern Europeans in the original triology. He is just a narcissistic nutjob in the mold of James Bond baddies.

And this is the point — this is, alas, the paradox of Lyotardian postmodernism. Live Free pretends patriotic fervor but comes up short. It believes but does not believe all at once. These platitudes precisely mirror an America seeking the old comforts, old notions of progress and goodness, but finds itself grasping only at straws. It finds the world to be a different place, a strange place, and does not yet know its new role. For its failings in drama, Live Free or Die Hard portrays the scattering of belief, an interregnum of ideologies, a world of uncertainty and danger.

The trailer for the forthcoming Rambo movie, which features the return of another old action icon, previews the next stage in American action rhetoric. Rambo, aiming his sights over his arrow, pontificates his portentously memorable tagline, "Live for nothing, or die for something." Stallone is right — what is left to live for when the fight for freedom comes up an empty promise — a nothing? At best the disillusioned American hero can grow from the experience of empty warfare, and does what he does best — survive the most improbable odds.

Mitch Finn, MA, is a psychotherapist practicing in Houston, and is currently a doctoral candidate in Mythological Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute. His masters thesis, Lessons from the Dark: Trauma and Soul Retrieval in Horror Cinema, examined the cultural fascination with horror mythopoesis. Mitch Finn, MA, is a psychotherapist practicing in Houston, and is currently a doctoral candidate in Mythological Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute. His masters thesis, Lessons from the Dark: Trauma and Soul Retrieval in Horror Cinema, examined the cultural fascination with horror mythopoesis.

Read more by Mitch Finn at his website mitchfinn.com

Read more articles by Mitch Finn in Mythic Passages

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|